When Fred Huntress looks back on his much-younger self, he just has to laugh.

“When I was in high school I wouldn’t even talk on the phone,” he says. “Gosh, it took me a long time to get out of that shell. Now you can’t stop me from talking.”

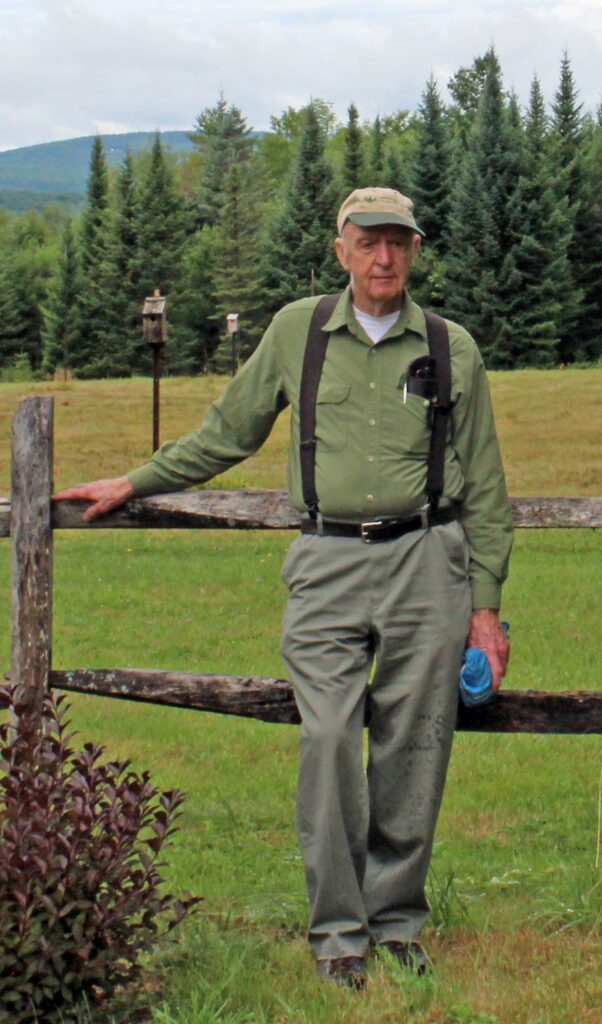

Why would anyone want to stop him? At 82, Huntress has seen much and learned more. He cares deeply, but pulls no punches. You can read his character in his straight back, square shoulders, bright eyes and half-skeptical smile. Compare a photo decades old with one taken yesterday and he’s hardly changed.

“There is no guile, there is no ruse,” says Ted Johnstone, former executive director of the Maine Forest Products Council. “What you see is what you get. Fred is a very upfront, genuine and honest person – to a fault.”

Huntress sometimes complains age has affected his memory, but in truth he’s forgotten little, especially where Maine’s forests are concerned. His interests are wide-ranging and his home office in Poland is crammed with books, newsletters, magazines, reports and information of every kind. It’s easy to believe him when he says he never throws out a thing. When he talks about Maine’s forest economy, his memories are so vivid you feel you were there with him, watching its evolution for more than six decades.

“There were no big sawmills when I started,” Huntress says. “Every town pretty near had a little pine mill. Two or three in South Paris. Bethel had, I think, three pine mills. And from Norway-South Paris, right up through Woodstock, Greenwood, Bethel, Rumford, Dixfield, Farmington, there was just a steady line of hardwood mills. And they’re all gone. I’ve got a book somewhere, that the state published back in the 1970s, and it had changed even before that.”

Huntress is celebrating his 50th year as a member of the Maine Forest Products Council and is still very active. He likely holds the record for the longest tenure on the Council’s Board, including a stint as president from 1983 to 1985.

“Everyone else was from paper companies and sawmills and I figured I had to be the voice of the small woodland owners and that’s what I still try to do,” he says.

He’s also served on the SWOAM Board and as a town selectman, planning board member, Conservation Commission chair, and town forester in Poland.

“His experience is deep, and his perspective is conservative, but balanced,” says Peter Triandafillou, who serves with him on the MFPC Board.

Huntress jokes that he has “glue on his feet,” because he was born in Auburn, the son of a mill (Pepperell) superintendent and farmer’s daughter. He moved 12 miles to Poland and stayed put for a half century. In one sense, he’s come a long way from the teenager who was afraid to talk on the phone. In another, his perspective is still the same as when he roamed the woods near his family’s Winthrop camp, became an Eagle Scout and fell in love with Maine’s forests.

“I decided to go to the University of Maine to study forestry. It was the only thing I wanted to do. I had no other ambitions,” Huntress says.

Ken Hancock of Hancock Lumber, a long-time client and friend, persuaded him to join the Council in the mid 1960s, which introduced Huntress to a wider world of political action. He spent his early years quietly watching and learning from the legends of the forest industry, including Albert Nutting, Austin Wilkins and John Sinclair.

“These guys were real gems –100 percent sincere and terribly knowledgeable people. They grew up in the woods,” Huntress says. “These were people who knew what they were talking about and they were well respected. They’d go to the Legislature and boy, people listened to them.”

Now legislators and many others listen to Huntress. He will never Google his name – he has no use for computers – but anyone who does will see it in scores of newspaper articles, often accompanied by phrases such as “widely respected,” and “renowned Maine forester.” He won MFPC’s Albert D. Nutting Award in 2010 and was named the New England Forestry Foundation’s Distinguished Forester in 2012.

“I quickly realized that Fred had an encyclopedic memory for all matters that were forestry related and that by simply listening to him I could learn a lot,” says Terry Walters, a colleague on the MFPC Board. “I found him to be a great source of information on everything from blister rust control, consulting forestry, Big Trees in Maine, forestry referendums and surveying. Fred was particularly enlightening on the politics of natural resource management in Augusta.”

He’s tackled many issues over the years, including Dickey-Lincoln Dam (opposed), Tree Growth Tax (passionate supporter), sprawl (against), land conservation (for) and wind mills on mountaintops (against). Right now he’s an actively opposing the proposed national park in the Katahdin region and fighting hard for the Land for Maine’s Future Program. He’s written many op-eds and letters to the editor and he’s not shy about telling Maine’s leaders, including the governor and congressional delegation, if they’re off track.

Bill Vail, former MFPC executive director, used to refer to Huntress as “a grumpy old man,” a description that still makes Huntress laugh. Vail, who now chairs the LMF Board, eventually figured out that Fred’s grumpiness “was directly related to his proximity to the Legislature, not the world in general. I developed the same condition myself.”

“I really admire Fred,” Vail adds. “He is a great forester and an outstanding guy. His knowledge and respect for Maine’s forest resource is truly remarkable. Fred is a very skilled naturalist as well, a real woodsman in the best sense of word.”

Straight out of Edward Little High in 1951, Huntress spent three summers working on Maine’s white pine blister rust control program and another summer at a lumber camp in Colorado. In 1955, forestry degree in hand, he got a job with the Eastern Pulpwood Company in Calais, a subsidiary of St. Croix Paper. By noon of his first day, he was in Canterbury, N.B., working with a crew of Canadians to brush outlines, cruising timber, mark boundary lines and locate roads.

“The way we located roads then,” he explains, “was they gave the forester a long-handled shovel and said, ‘Go find some gravel somewhere.’ So I’d take off on a Monday morning with food for the week and stay in a camp that one of company people owned somewhere in the woods. I learned where I thought gravel could be by just looking at the topographic map and digging a helluva lot of holes.”

He also met Shirley Sanders, who he married Dec. 10, 1955, at St. Stephen, New Brunswick. They returned from their honeymoon to find his draft notice waiting. It’s impossible not to laugh when Huntress describes his complete lack of interest in surveillance radar, where he was “on the ground floor of computers and didn’t even know it.”

“No, I was a forester,” he says emphatically. “I didn’t want anything to do with computers and radar! So I ended up in Inchon, Korea, with an M1 carbine on my back, guarding the pipeline. That was all they could find for me to do. That was the end of my military career.”

He’d been home a month when he was hired as a consulting forester by the New England Forestry Foundation in 1958, a job that lasted full-time until 2001 and part-time even longer. Later he added surveyor and real estate broker to his job titles, realizing that he “could do everything for my clients,” including manage their land, survey its boundaries and sell it for them or their heirs.

“Sumner Burgess, the chief forester for Oxford Paper, said I was the first seller/broker, who ever knew anything about the land,” Huntress recalls. “This glamorous real estate broker sold them a big piece up in Highland Plantation and he said, ‘She’s better looking than you are, but she didn’t even set foot on the land.’”

His real estate commissions allowed him to buy land of his own, something he advises every forester to do, if only to learn about consequences.

“Working other people’s land, you’re going to make totally different decisions than you are working on your own land,” Huntress says. “I think it’s done me a heckuva lot of good because most foresters never see the consequences. They plant trees and they never know whether the trees lived or died.”

He decided to officially retire three years ago, more than six decades after he got his first job on the blister rust program in 1951.

“Too old. Too tired. Oh, I just couldn’t physically keep up with it,” he says, then adds with a note of irritation. “And it was too much computer stuff. It was computer this and computer that.”

Triandafillou admires Huntress’ ability to run a successful business without email or internet access, but respects even more the loyalty he earned from his clients.

“I believe that if he told his clients that tomorrow was the day to walk off a cliff, they’d ask him when and where to show up,” Triandafillou says.

To Ted Johnston, Huntress was a man far ahead of his time.

“Fred has been practicing sustainable forestry since he became a forester,” Johnstone said. “He helped small landowners manage their land so they get a little income, a little enjoyment. He helped them realize the multiple values that come out of the forest. He’s always been a great listener, but most importantly, I think, is just his love for the forest.”

As a 2012 Sun Journal story noted “Fred Huntress knows as much about growing trees as he does about cutting them down.”

His license plate reads “BIGTREE,” but it isn’t just big trees he loves. He’s a tree connoisseur. He worries deeply about white pine (“Once you cut pine, it takes heroics to regenerate pine.”) and he’s determined to establish white oaks across the state, including donating one each year to MFPC’s annual auction. He’s even got a soft spot for black gum, which grows mainly in swamps and has value only as pulpwood.

“I own almost the only black gum in Poland,” he says proudly. “I’ve got a dozen of them over here in one woodlot. To me, they’re a rarity. I wouldn’t cut one.”

If you’re wondering if Huntress is spending his retirement rocking on a porch, think again. He misses his wife Shirley, who died in 2011, very much, but enjoys time with his daughter, Dr. Laurie Huntress, son-in-law, Joshua Hounsell, and granddaughter Alexandra, who live nearby. He’s also happy managing their forestland and his own.

“I own a little over 1,000 acres in six different towns. That’s enough to keep me busy,” he says. “It’s more than enough to keep me busy. More than I can handle probably.”

Last summer, he celebrated the 50th anniversary of his purchase of 210 acres on Rattlesnake Mountain in Raymond. Once he could run right up and right down that mountain, but now he walks a little trail he’s made. He’s thrilled at how the white oaks have multiplied and a while back he discovered a little spring coming out of the rocks, ice cold. One day – one of the best – he painted almost 3,000 feet of boundary land and came home so tired he could hardly walk.

Behind his house is a long view of a beautiful stand of white pine, out front is a tall white oak and his four-wheeler can take him through many acres he’s managed for many years.

“I’m lucky,” he says. “I can look out my window here and see hardly a house,” he says. “I’ve just watched it grow all these years and I love it.”